Driver Assistance & the Path of Most Resistance

Original in November, 2020 | Revised in June, 2025

Drivers do not want to crash, nor should they. Features that provide Driver Assistance and comprise Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) are in demand and on the rise. Consumers understand “emergency braking” and “crash prevention” as available features and these features are increasingly becoming a primary purchase (consideration) factor for new and newer used vehicles. Many would say that they are the most important features in modern vehicles. They may also be the most concrete implementation of an intelligent system of sensors and software that has a direct cause and effect on our daily lives. The Driver Assistance (DAT / ADAS) functional domain is the cognitive on-ramp to autonomous comfort and trust. Or as the folks at J.D. Power like to put it, “Today’s experiences with a technology drives tomorrow’s desire.”

Unfortunately, our understanding of how these features operate and our general consumer opinion of them is not as positive as it should be. Past surveys by JD Power reported that 23% of vehicle owners with Lane-keeping or Lane-centering systems found them irritating. Not too long ago, the Center for Automotive Research (CAR) proclaimed that 60% of people with automated driver assistance systems are turning them off. A recent UK study found that 46% of drivers turn off intelligent Speed Assistance (ISA) features, now mandatory for new cars sold in the EU. Nationwide Insurance states it succintly that, “In today’s high-tech automotive world, the challenge isn’t necessarily getting the features that you want; the challenge lies in understanding and mastering the features you have.”

If consumers actively search for and deactivate a feature before every drive (proclaiming them to be useless), then you have a design failure. If consumers find parts of your product intrusive, or irritating, or confusing, then you have a design failure. If consumers believe that certain features are dangerous and may actually contribute to more accidents, then you have a design failure.

Find more specifics on ADAS deactivation on the STATISTICS page.

The competitive hype and diverse Marketing of these systems continue to grow as does consumer interest, but not consumer comprehension or long-term perceived value. As the years pass and complexity persists, negative sentiment is increasing. We seem to be stuck in a holding pattern of limited understanding and appeal – despite the addition of 3-dimensions of visualization, more realistic vehicle renderings, high resolution, detailed pop-ups & feedback, partial hands-off driving, motion graphics, lane changing and more incremental functionality and visual enhancement. The functional segmentation is an issue as is the signaling - as beeps, chimes, and related audible warnings are often referenced as one of the biggest detractors.

Most new vehicles will soon be equipped with the sensors and software to support advanced driver assistance, but you are going to have to incrementally pay for the next great feature enhancement to those systems. If consumers do not like or understand what they are getting today, then will they be willing to pay for more functionality on the same base experience? As we know, humans have been programmed to crave the next new tech - even if it will make our lives more complex. Offering full hands-free self-driving seems to be the required leap. Over time, I expect that another category of valuable upgrades will be the ones that just make these complex features easier to understand and use. In many of our overly engineered product categories, consumer’s are willing to pay more for simplicity and clarity of function and operation.

Let’s examine some root causes. What follows are some broader thoughts on how we got here and the approach that we might take to fix things. Step back and consider …

Should we only design manually driven systems and those that are fully machine controlled (and skip the messy middle)?

Should we be selling driver assistive systems that at times (when active) allow the driver to operate hands and feet free, but may at any time, due to changing conditions around them, demand that the driver take full control of the vehicle?

Should we be designing and delivering features that automatically drive the vehicle with limits without maintaining an awareness of the state of the driver?

Should our primary goal be to “design for distraction”? Via a Pew Research Center study, 46% of adults admitted to reading or sending text messages while driving.

Should we be delivering features that regularly do something that was not expected or explainable? (not so different from the history of in-vehicle voice recognition / assistance)

Should we be enabling so much user input, variability, and layers to the way that an assistive system operates? (like following distance, speed control, amount over / under posted speed, sensitivity levels, minimum operation speeds, eyes off road limits, etc.)

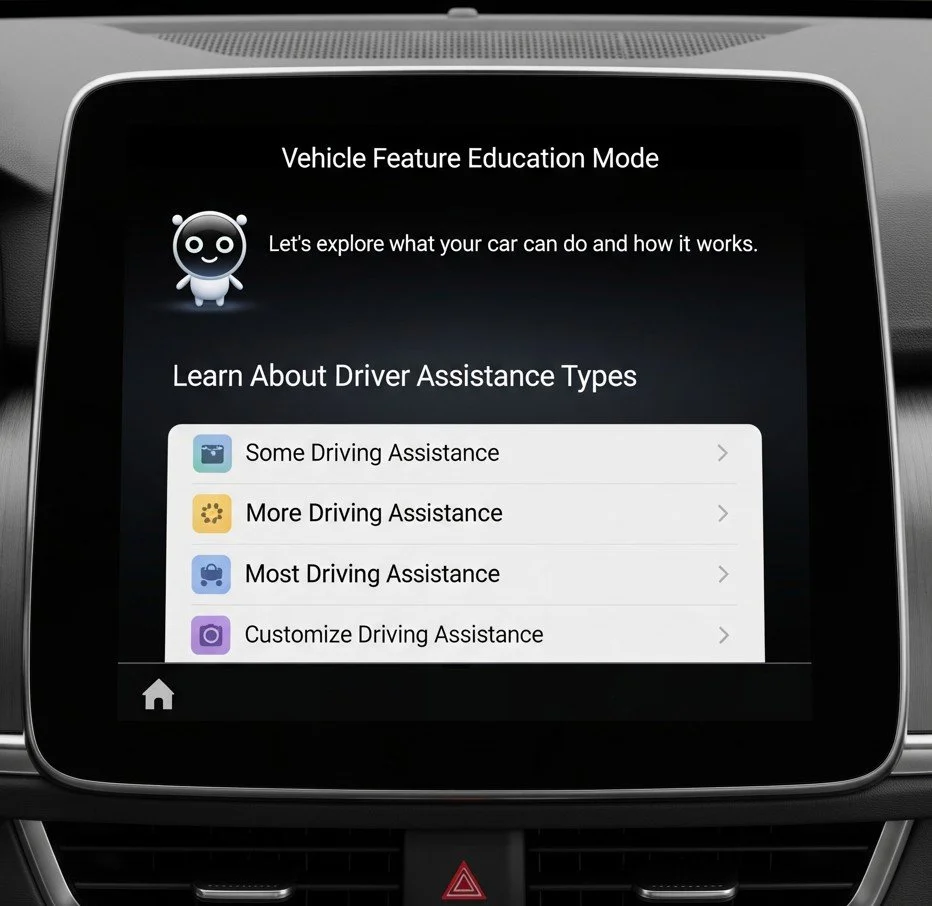

How about Good, Better, and Best levels of assistance?

Will these partially effective and partially understood features do more harm than good to a brand in the long run? How about to the auto industry as a whole?

The answer to better understanding, acceptance and perceived value of driver assistance systems lies in rethinking the metaphors. We have lanes, distance, traffic (other cars, trucks, motorcycles, bikes, pedestrians, etc.), and speed that we can control and that the vehicle reacts to. It is a new and different driver experience when the vehicle is reacting to all of these factors continuously while driving in traffic, which is most of the time. The vehicle is constantly pushing and pulling, correcting and assisting - and despite the consistent use of adjectives like Gentle and Natural, the experience most time is not that. It is safe to say that a whole list of incremental feature upgrades (like staying in the lane and nudging over a bit when passing) are progressing the systems towards a feeling of more “Familiar, Natural, or Comfortable”. However, unless automated systems are perfectly mirroring my behavior based on my complex thoughts as I perceive dynamically changing contexts, then these features will never be “Natural”. It is probably impossible to tune & program the complex multidisciplinary driver assist systems (including mechanical, electrical, computer engineering, complicated software and algorithms) to perfectly reflect my comfort levels with dynamic spacial awareness, speed and position at each moment.

The sequence. First, we have to activate these functions in a way that we think fits the context and our immediate needs. We push buttons and expect them activate certain vehicle capabilities and subsequent behaviors. Sometimes it is one function at a time, sometimes it is a few functions that are activated, and sometimes it is a larger group. Then while driving, if a lane is touched (or) a lane vanishes or shifts (or) the vehicle in front of you moves out of the way or breaks suddenly, then the vehicle signals the driver in numerous ways (using lights, symbols, sounds and more) and at the same time, the vehicle physically adjusts its behavior. It is a lot to ask a driver to anticipate and understand each of these variables and make functional choices. Five different things can happen in five seconds. It is natural to want to know and understand the cause and effect of our choices and actions. Not to mention that these behaviors may be “upgraded” while you sleep and experienced differently on your next drive.

If the vehicle is “driving itself” and you are able to take your hands off of the steering wheel and your feet off of the pedal, then you should not have to be looking forward at the road all of the time. The expansion of partial self-driving routes and adding lane changing capabilities are incremental steps to full automated driving. Is freeing your hands but not your eyes a compelling value proposition? These are just a few of the functional enhancements and awkward and unnatural user requirements that are being introduced as the systems progress towards Level 5. The problem is that new car buyers are suffering confusion, self-doubt, and frustration as OEMs charge for incrementalism. Even the actor in the Nissan commercial using ProPILOT looks anxious as he goes into “Chill mode” and drives with his hands slightly off the wheel and foot off of the pedal.

On Comprehension

Almost half of the consumers that drive a vehicle equipped with driver assistance features, do not clearly understand how they work and/or do not perceive them as valuable. Or as Tech Crunch referenced in 2019 headline, “Study finds drivers are clueless about what driver assistance systems can (and can’t) do.” Like many advanced features in vehicles today, drivers have notions and expectations of what a feature does, but it is rarely completely accurate. And this has proven to also be the case for many that receive real-time instruction from the system. It is important to stress “complete accuracy” because partial understanding can sometimes be worse than no understanding and can lead to wrong assumptions that have grave consequences.

What buttons do I push to initialize the system?

What is the sequence of buttons to push?

Why does that feature not work in this Mode?

What are the relationships & dependencies of the collective cluster of buttons?

How do I adjust the speed - and the ability to lock onto / avoid the car in front of me?

Doesn’t it automatically set to a safe distance from the car in front?

Why does it automatically gradually stop the vehicle sometimes, but not others?

Why do I have to make so many choices about how these features behave and react?

How do I set a max speed or set a max over or under the posted speed?

What do those multiple beeps mean?

Why do telltails and icons occassionally turn colors that make them unreadible?

Is it working? Why did my car just do that? (You get the gist)

Frequency of use matters for learning and comprehension. These features have been mostly designed for highway driving because those conditions are easier to master - even though most of our time is spent driving on neighborhood streets or in cities and towns. Consumers need to adopt a mindset of “trial and error” and a willingness to experiment with these features to really understand what they do and the nuances of how they do it. It is becoming more prevalent for new owners (who are also content creators) to conceive of every potential “use case or edge-case” of a feature and then simulate, record and explain the system’s behaviors on YouTube, TikTok and elsewhere. The quantity and detail of Tesla feature behavior videos online is exhaustive, easily found and highly educational. Coincidentally, Tesla Autopilot is preferred by consumers in measures of “ease of use” (versus) Consumer Reports high ratings of Ford BlueCruise and GM Super Cruise.

I propose that these consumer misunderstandings, wrong assumptions and points of confusion in regards to driver assistance are fundamentally a design problem. The addition of a universal Assist Off button is an admission of an OEM’s failure. However, it is a complex problem – one that involves fixing many things - like their functional definition and operation, internal organizational structures, business process modeling, feature marketing, decision making process, the user interface and probably more. Industry competition, engineering-driven cultures, population safety and human mental models seem to be at odds.

That’s Mr. Co-Pilot to You

The names may sound similar - Adaptive Cruise, Auto Cruise, Lane Keep Assist, Active Navigation, Lane Centering, Highway Assist, Speed Limit Assist, Traffic Jam Assist, Lane Tracing, Drive Pilot, Driver Assistant Plus, ProPilot Assist, Super Cruise - however, these features do very different things. Some slow the vehicle down, some speed it up, some move it over in a lane, some lock it a set distance from the vehicle in front of it or to the center of the lane while others drive the vehicle completely at low speeds. Most OEMs are chasing more or less the same features and vehicle behaviors; however, these same features in vehicles of different OEMs have different vehicle behaviors (and) are operated differently by drivers. Not to mention that the variations seem to be increasing as OEMs and suppliers strive to satisfy the various “Levels of automation”, which consumer’s don’t understand or care about anyway.

We seem to be traveling the path of most resistance of getting to a point where it is safe to take a nap when any of these features are activated.

from Consumer Reports, Auto Safety Report

And if you don’t understand the individual feature, then you most likely will have even more trouble when your vehicle is acting in accordance with a second or third activated feature related to it. And just to pile on, some of these features have a relationship or dependency on each other and even another layer of adjustment when activated. It sounds confusing because it is. And if you can’t figure-out how to adjust it to your liking or maybe just your tolerance, then you turn it off. As a Consumer Reports analyst put it, “The needlessly complex interaction of multiple systems on the same vehicle adds to the confusion.” Ambiguity and unpredictability are the enemy of acceptance. Without acceptance, there will never be trust or desirability.

A lot is at stake because the progressions and promises of “autopilot” technology and self-driving systems (and their clear consumer understanding and desire) are as mentioned, probably the most important features for OEMs to get right. It is not that the OEMs do not know what consumer’s want or how they perceive or think about these “assistive” features, they do. Unfortunately, the progressive competitive technological march that they have been on for decades has resulted in these overly complex systems. It is almost impossible to undo the complexity of sensors, code, modules, interfaces, signals and more that got them to this point of functional capability and incremental parity.

It may also be impossible to undo the market value, communication strategies and internal cultures that support these paths. The variables, factors and choices made by each OEM include the types of sensors, what level of awareness each vehicle has, the computational power allocated, their short, mid and long-range technological capabilities and how they translate into features and then are positioned and released. Not so often mentioned are the high service costs and the lessening of our own abilities that result from partial automation. As Consumer Reports stated, “As driver tasks are removed, a driver is more likely to lose situational awareness and could be more easily distracted.”

On Driver State Monitoring / On Driver Awareness

The advantage of monitoring the driver with cameras and/or sensors is to recognize distraction, drowsiness, lack of attention or even consciousness so that the vehicle can intercede if needed. If the driver is distracted by their mobile phone and a text message and a stop is approaching, then the vehicle should pre-condition or pre-load the breaks to make an evasive maneuver or stop abruptly. Perhaps a vehicle recognizes that the driver is distracted and “ratchets-up” the level of potential notification - including distance, volume, visibility and other multi-sensory cues.

The systems that are going in new vehicles today are a significant investment in driver attention monitoring and are there mostly to check if the driver occasionally glances “eyes forward” or on to the road. You can drive hands-free, but you need to be awake and looking forward. And with a little bit larger investment, these systems could tell if the driver is eating, drinking, reading a book, sleeping, grooming or doing one of many other already recognizable and identifiable behaviors.

Vehicle fleets, their managers and their suppliers are leading the way to making driver’s more aware and accountable while at the same time giving management vast amounts of data and visibility. They are employing tactics like …

Identification of risky driving behaviors like mobile phone use, eating, drinking, smoking, not wearing a seat belt, speeding and general inattentiveness

Identification of unfocused driver attention or fatigue or drowsiness

Tracking and quantifying both the duration and the percentage of drive time of risky behavior, therefore better understanding the persistent risk

Providing access to their own driving records, videos (if opted-in) and stats for reflection, self-improvement and self-correction

New Domain Metaphor + AI Assisted

Steering, breaking & accelleration modulated by context sensing. One of a few concepts to explore.

Also look towards the design of micro-mobility vehicles and management services for insights into alternative feature design and new paradigms of interaction. While fleet vehicles provide a greater degree of driver and vehicle monitoring and analytics, micro-mobility vehicles have an increased speed to market, a flexibility of implementation, ease of upgradability, and a mindset of experimentation and improvement from generation to generation. Improvement comes to these systems in weeks and months rather than years.

Considerations for the Future

The sensors are installed and the software can be fine-tuned, but the functional logic and grouping, how the process is defined, and the required human operations need to be improved. This always starts with a better understanding of humans - what they want and need, how they think about these features, how they anticipate them to work, why they turn them off, how they work-around problems and more. This is a collaborative, multi-disciplinary, user-centered design problem that requires tenacity, investment and an enterprise-wide commitment to fix.

What’s next consideration: Multiple modes working in coordination while recognizing patterns and learning.

These DAT systems continue to incrementally step towards more natural human behavior, but are still a long way off. As I cruised around 10 mph for a few miles, what struck me was the opportunity to smoothen the collaboration – with the machine / vehicle doing most of the work and the human (me) dropping subtle commands or hints to fine-turn actions. In these cases, for voice commands and interjections to supplement the advanced driver assistance system. “Stop on Yellow.” “Do not cross.” “Let them in.”

As I drove (er, cruised) the length of the 2025 Woodward Dream Cruise this past weekend with advanced driver assistance (ADAS / DAT) enabled, the patterns of disengaging and reengaging (and what was missing) became quite clear.

The system recognized traffic signs but not traffic signals. I know that this feature is in Tesla FSD and coming to others. BTW, I like to slow-down and stop on yellow lights.

The system did not react to police officers. The vehicle did see them but did not recognize or react. No doubt, “people in uniforms” recognition is coming soon.

The system did not know to Not block an intersection when forward vehicles were backed-up to the other side of the intersection. The vehicle did see the vehicle directly in front of me and did recognize an intersection.

The system did not know when and how to be courteous to other drivers. I had to disengage to let them into my lane. The vehicle did see them heading into the intersection.

I anticipate that the commercial fleet world will lead the way in driver recognition, behavior modification of both humans and machines, and in the definition of intervention protocols. These commercial efforts (which include traditional automotive suppliers and software companies) will also lead the way in defining new paradigms of man-machine interaction. It is safe to assume that a Digital Assistant or Virtual Brand Agent may soon be doing more intervention as well as the actual driving. Some additional areas of exploration for the future might include …

The use of audio tones as the primary feedback for state of driver assistance features

A dedicated highway lane for vehicles with “pilot-like” assistance capabilities

One button or control interaction for On / Off, Disengagement / Engagement during a drive session. Do lane and speed controls really need to be separate? Should I chose my preferred distance from the vehicle in front of my (or) should the optimal safe distance be established by the vehicle?

Activate automatic engagement based on context and patterns of behavior and flow (like the Segway eMoped C80 Auto Cruise feature)

Automatic accommodation of driver systems to the attachment of diverse trailer type - sensing load sizes, balance and weight distribution

Build-on and constantly improve the “always on” state and put much more focus, investment, and effort into the comfort of “collaborative driving”

If my phone is “acting-up” (or) my laptop starts to slow-down (or) my vehicle’s infotainment system freezes, then I perform a “reboot”. It’s interesting that that is still the go-to fix for so many of us. And if you and I have ever worked together, then you know that I like to blame the $#!@ Fairy for causing (mostly digital) breakdowns. Despite knowing the system and maybe the organizational and financial reasons why things do not work as expected, it is always easier to blame fairies. But not in this case. It may be time for that proverbial Reboot (or said another way, a Creative Leap) in the planning, architecting, enabling and functional presentation of Driver Assistance. Increase the pace and importance of structured consumer understanding, prototyping, feedback loops, and constant improvement. Reduce the friction of mass consumer ADAS adoption and realize the investment in share of trust and loyalty. The viability and customer acceptance of future EVs and AVs may depend on it.

These opinions are mine alone and do not represent any OEM, Supplier or any other company in the Automotive or Mobility industries. Sources of valuable information on these topics that informed these ideas came from JD Power, IIHS, the University of Windsor, Human Systems Lab, Euro NCAP, Consumer Reports, NHTSA, Pew Research Center and recent survey’s on Reddit.

movotiv

Product, Service & Emotional System - Design Consulting, Advising & Collaboration